Christchurch is not a city that performs for visitors. It does not overwhelm with spectacle, nor does it curate itself for instant gratification. Instead, it reveals itself slowly—through land, infrastructure, history, and conversation. That becomes clear the moment you sit down, coffee in hand, in the gardens of Chateau on the Park and begin talking to someone who has lived the city from the inside. Christchurch is often described as the most “English” city in New Zealand, but that shorthand misses what actually defines it. This is a city shaped by settlement decisions, seismic consequences, social memory, and resilience under pressure. It is flat because it was built on swamp land. It is orderly because it inherited British systems. It is cautious because it has been physically broken before. You don’t understand Christchurch until you understand what it has endured—and how it continues to function anyway.

Our conversations with Dorothy Pickering, Commercial Manager at Chateau on the Park, offered a clearer window into Christchurch than any guidebook.

The hotel itself occupies five acres—an entire city block—yet feels removed from the city despite sitting close to its center.

“We take over the whole five acres for the whole city block—and each part is slightly different: the rose garden, the village green, and lots of different areas,” Pickering explained.

That spatial philosophy mirrors Christchurch itself: open, segmented, intentionally paced. You are never rushed here. Even the city’s recovery has unfolded slowly, deliberately, sometimes painfully so.

The hotel’s endurance through the earthquakes is not incidental—it is symbolic.

“We were really lucky. The buildings swayed and we got some cracking, but the hotel was fine.”

Christchurch was not fine. Large sections of the city were destroyed. Entire neighbourhoods were rendered unstable. Insurance battles dragged on for years, disproportionately affecting lower-income residents in the eastern suburbs. Many people settled for fractions of what repairs actually cost because they could not afford to fight.

Here’s where our conversation became uncomfortably relatable.

Steve and I have lived our own version of disaster recovery through hurricane damage and the insurance process in the United States. The manager described similar dynamics after the Christchurch earthquakes: insurers attempting to settle quickly, pushing people toward partial compensation, and creating long delays that were easier for the wealthy to endure than for those without cash reserves, legal support, or time.

This is one of the most under-discussed truths about recovery: Disasters don’t just damage buildings. They expose who has leverage.

If you have money, you can pay up front and fight later. If you don’t, you may be forced into the first offer just to survive. Christchurch lived this at scale.

This isn’t a Christchurch-only story. It’s a modern governance story—one where the moral language of “resilience” often hides the financial language of “who carried the cost.”

Christchurch’s earthquakes were not just geological events. They were systemic stress tests. Infrastructure failed. Insurance systems exposed their incentives. Social inequities hardened.

What stands out now is not trauma tourism, but normalization. The city does not dramatize its suffering. It absorbed it. Buildings that survived became anchors. Institutions that held—schools, parks, civic spaces—became symbols of continuity.

Christchurch Boys’ High School, for example, endured with minimal damage while other structures did not. It remains one of the city’s most socially coded institutions.

Pickering explained one of Christchurch’s most telling cultural habits:

“In Christchurch the first thing people will say is, ‘What school did you go to?’ so they can mentally click where you fit.”

That single question reveals how legacy, class, and belonging still operate here. Christchurch is not obsessed with status in a loud way—but it is highly aware of lineage, schooling, and networks.

That history lingers in the city’s temperament. Christchurch is polite, but it is not naive.

The building was designed by Peter Beaven, a major figure in Christchurch architecture. The hotel’s design is often described as a Gothic revival fantasy—deliberately theatrical, deliberately romantic, and not representative of all of his work.

That matters because Christchurch itself is a city where architecture is never just “pretty.” It’s political. After the earthquakes, rebuilding forced the city to make choices about what to preserve, what to replace, what to modernize, and what to admit was unsafe or unsustainable.

So when you stay somewhere that is stylistically assertive, you’re not just staying in “a nice hotel.” You’re staying in a built argument about identity.

Christchurch was settled by English migrants arriving via four ships that landed in Lyttelton and walked over the Port Hills to the plains beyond. The city inherited English naming conventions, Anglican institutions, school systems, and social stratification.

“Christchurch is seen as the most English of the New Zealand cities,” Pickering said. “A lot of people can trace their families back to the first four ships.”

That legacy explains the architecture, the school culture, and the sense of continuity that still defines the city. It also explains why Christchurch was built where it was—on swamp land that later amplified earthquake damage.

Good intentions. Poor geological foresight. Long-term consequences.

Christchurch’s geography is often underestimated. It sits between braided rivers, fertile plains, the Port Hills, beaches, vineyards, and alpine ski fields—all within close range.

From the air, the braided rivers look like fractures across farmland—visual reminders that water here does not behave predictably. On the ground, the city feels spacious and navigable, but never dense.

Pickering pointed out what many visitors miss entirely:

“A lot of people don’t see the bays—over the Port Hills: Corsair Bay, Cass Bay, Governor’s Bay, Diamond Harbour. It’s really pretty.”

These bays offer something rare: proximity without pressure. You can move from city to coast in minutes without losing calm. Christchurch does not compress experience the way many global cities do. That matters more than people realize.

Christchurch is best experienced on foot. Not as exercise. As orientation.

“Walk through the park, cross the river into the city, jump on the tram,” Pickering suggested. “It’s about half an hour and it’s really nice.”

This is a city that rewards walking because it was not designed around spectacle. The Botanic Gardens, Hagley Park, the Avon River, and the central city connect without friction.

Public spaces here still serve their original purpose: slowing people down.

If Christchurch is restraint, Akaroa is contrast.

“I would definitely go to Akaroa,” Pickering said. “It’s a little French settlement—cute houses, the wharf, and you can go see the dolphins.”

The drive over the hills reveals harbors that feel entirely separate from the plains. Akaroa’s French roots add another layer to New Zealand’s colonial mosaic, reminding visitors that this country was shaped by overlapping ambitions, not a single narrative.

Akaroa works because it is not overbuilt. It remains small enough to feel real.

One of the strongest signals at Chateau on the Park is staff continuity.

“A lot of our staff have worked here a long time. Our regulars know exactly what table they like, and what wine they’re going to drink.”

That kind of institutional memory is rare in global hospitality. It signals something deeper: Christchurch values continuity over churn.

That is not accidental. Cities that have been physically destabilized tend to anchor themselves through people.

Christchurch does not market itself aggressively. It does not need to.

It is a city where infrastructure, social systems, and geography are still in dialogue. Where recovery did not erase inequality but exposed it. Where beauty is quiet, not performative.

It is also a city shaped by global forces—climate instability, insurance economics, migration, and mobility anxiety. Conversations about borders, work permits, and travel uncertainty surfaced naturally in discussion, reflecting a world where movement is no longer frictionless.

Christchurch feels stable precisely because it knows what instability looks like.

Christchurch matters because it represents a future many cities will face: climate stress, infrastructure failure, insurance retreat, and social recalibration.

It shows what happens when cities are forced to live with consequences instead of rebranding past them.

It also demonstrates that recovery is not about spectacle—it is about systems holding under pressure.

Christchurch did not rebuild itself into something new. It rebuilt itself into something more honest.

And that honesty—quiet, grounded, unadvertised—is exactly why it deserves attention now.

We went to Christchurch for travel. We left with a clearer understanding of systems.

The hotel conversation gave us three real insights:

If you’re deciding whether Christchurch is “worth it,” here’s the answer:

Yes—especially if you care about how cities actually work after something big goes wrong.

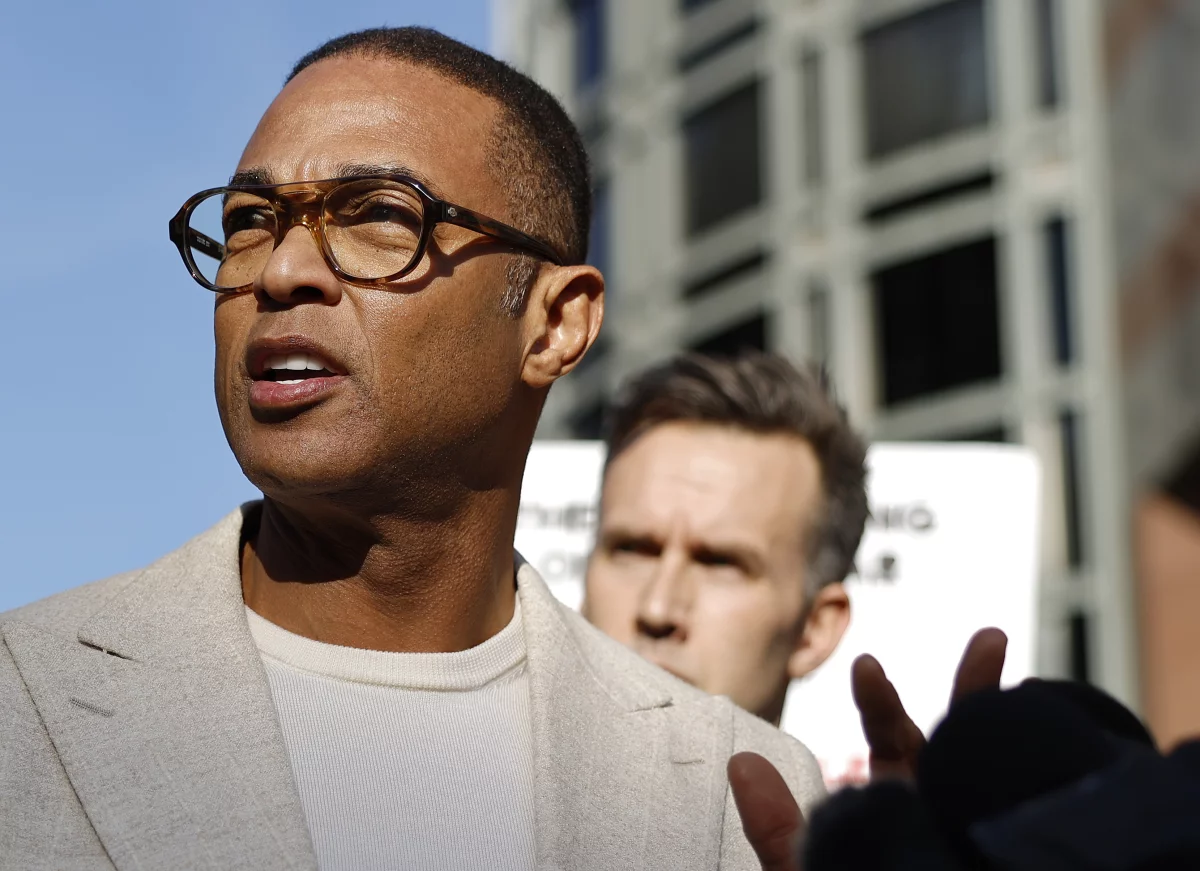

The arrest of a high-profile journalist is not an isolated legal event. It is a systems signal. This editorial examines the growing global pattern of prosecuting journalists under the guise of law enforcement, the erosion of First Amendment protections in practice, and why democratic societies fail when witnessing becomes a punishable act.

On March 21, Naples, Florida will host TEDx Naples—one of thousands of independently organised TEDx events held globally each year. On the surface, that might not sound remarkable. TEDx events are common. Many are forgettable. Some are performative. A few are genuinely consequential. This one has the potential to be the latter. At a time when public trust in institutions is low, civic dialogue is fragmented, and leadership conversations are increasingly reduced to slogans, TEDx Naples is positioning itself not as entertainment, but as a forum for adult thinking—about responsibility, justice, resilience, and what it means to lead in a world shaped by consequence rather than applause. This editorial explains why this particular TEDx event matters, what differentiates it from the broader TEDx ecosystem, and why its timing—and location—are not incidental.

What looks like cultural chaos—celebrity outrage cycles, travel exhaustion, and climate anxiety—is actually one interconnected signal. Entertainment, mobility, and climate stress now operate as a single feedback loop, revealing how systemic overload shows up first in culture before it appears in policy or economics.