The arrest of a high-profile journalist is not an isolated legal event. It is a systems signal. This editorial examines the growing global pattern of prosecuting journalists under the guise of law enforcement, the erosion of First Amendment protections in practice, and why democratic societies fail when witnessing becomes a punishable act.

When journalists are arrested, the charge rarely tells the full story. The signal does.

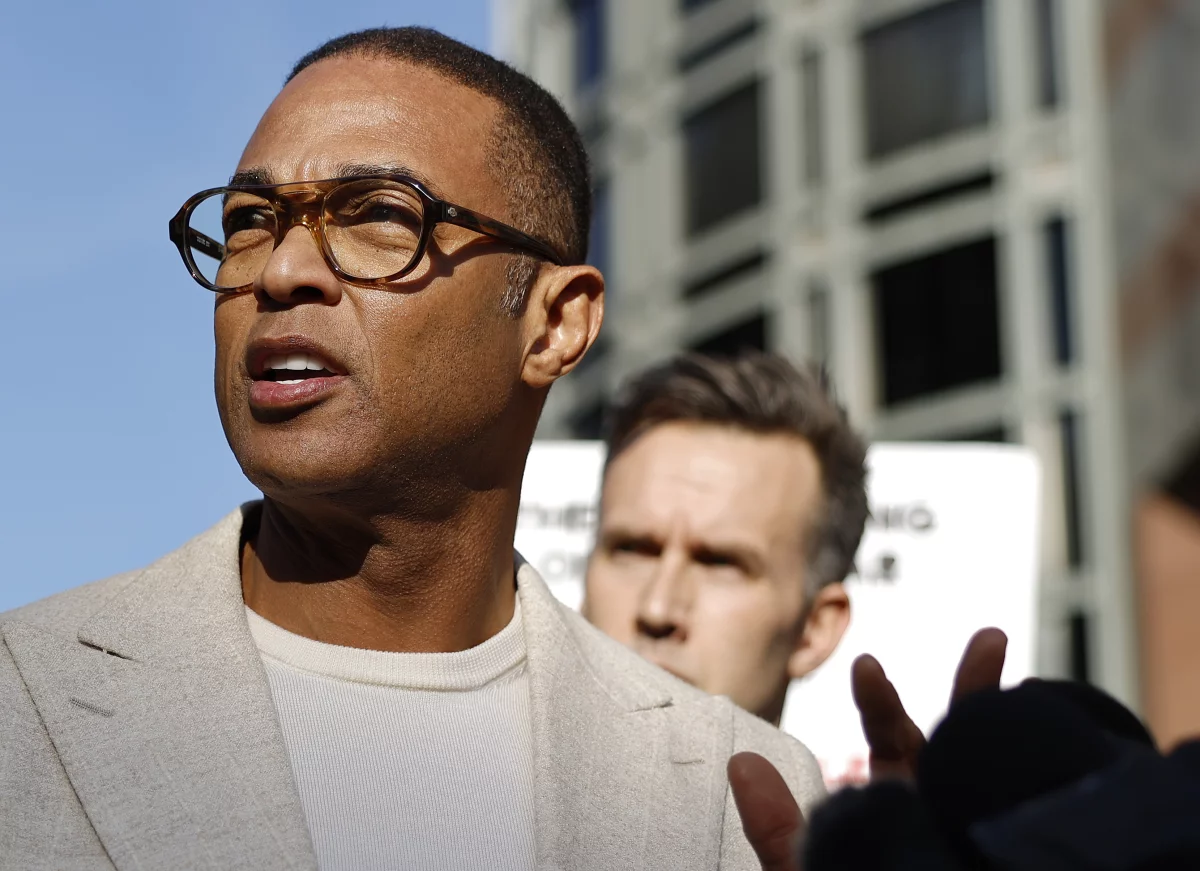

The recent arrest of Don Lemon, as reported by CNN, amplified by outlets such as Variety, is not significant because of the individual involved. It is significant because of where the arrest sits in a broader pattern: the tightening boundary between journalism and criminal liability.

Across the United States and globally, journalists are increasingly treated not as witnesses to public events but as participants subject to punishment. This shift does not require overt censorship. It operates through selective enforcement, legal ambiguity, and procedural intimidation.

The issue is not whether one agrees with a journalist’s reporting, tone, or politics. The issue is whether a democratic system can function when those who document power are punished for proximity to it.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is explicit: Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press. In theory, this is absolute. In practice, it is conditional.

Over the last two decades, legal protections for journalists have been eroded not by constitutional amendment, but by operational drift:

According to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, journalist arrests and detentions in the U.S. surged during periods of civil unrest, particularly after 2020.

What has changed is not the law—it is enforcement posture. Journalists are now routinely asked to prove neutrality after being detained, rather than being presumed protected before action is taken.

The specifics of the Lemon arrest matter less than the structure surrounding it. According to statements released by CNN and corroborated by court findings referenced in Minnesota federal proceedings, judges previously found no evidence of criminal behaviour related to journalistic activity in the same protest context.

This is critical. When courts deny warrants due to lack of evidence, yet arrests occur later under different jurisdictions or procedural tactics, the outcome is chilling even if charges do not hold.

This is known in legal scholarship as process punishment—the idea that arrest, detention, and legal defence become punitive regardless of conviction.

Harvard Law Review has documented this phenomenon extensively.

The message to journalists is clear: even if you are right, the cost of being right may be high.

The criminalisation of journalism is not new. It is historically predictable.

The United States is not immune to structural drift simply because it has stronger institutions. Democracies do not collapse when laws change; they weaken when enforcement becomes selective. Political scientist Steven Levitsky notes that modern democratic erosion occurs through “legal but abusive practices.”

A key modern tactic is the conflation of journalism with opinion. When reporting becomes labeled as “activism,” legal protections weaken. This framing is strategically useful because it reframes journalists as participants rather than observers.

However, courts have historically rejected this distinction.

The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly held that motive does not negate press protection. The act of bearing witness—documenting, recording, questioning—is protected regardless of tone or perceived alignment.

Yet public discourse increasingly treats journalists as ideological actors first and civic infrastructure second. This cultural shift enables legal risk.

Federal involvement in journalist arrests carries symbolic weight. It signals national tolerance for local suppression. The Department of Justice maintains internal guidelines discouraging prosecution of journalists absent extraordinary circumstances.

However, guidelines are not law. They are discretionary.

When enforcement agencies ignore precedent without consequence, the guideline becomes performative rather than protective.

This creates a two-tier system:

According to Reporters Without Borders, press freedom declined globally for the seventh consecutive year in 2024.

Notably, declines are no longer concentrated in authoritarian regimes. Democracies now account for a growing share of legal harassment cases.

The common pattern includes:

This is governance by deterrence.

From a systems perspective, punishing journalists serves three functions:

Importantly, this strategy does not require winning in court. It only requires changing behaviour.

Perhaps the most dangerous factor is public indifference. Many citizens view journalist arrests through partisan lenses—supporting or condemning based on alignment rather than principle.

This is structurally fatal. Press freedom does not protect journalists; it protects the public’s right to know. When citizens fail to defend it universally, it becomes conditional—and conditional rights are temporary.

If current trends continue, several outcomes are likely:

This weakens not only media, but courts, elections, and public trust. Democracy requires witnesses. When witnesses are punished, power becomes opaque.

This moment is not about Don Lemon. It is about precedent.

Every journalist arrested under ambiguous circumstances redraws the boundary of acceptable power. Every prosecution normalised becomes the next justification.

The First Amendment does not erode overnight. It erodes through exceptions. If journalists are no longer safe to observe power, then power no longer fears accountability.

That is not a media problem. It is a governance failure. History is clear: societies do not lose freedom when speech is banned. They lose it when speech becomes dangerous.

The line between journalism and criminality is not a legal technicality. It is the line between transparency and control.

Once crossed, it is rarely restored without consequence.

On March 21, Naples, Florida will host TEDx Naples—one of thousands of independently organised TEDx events held globally each year. On the surface, that might not sound remarkable. TEDx events are common. Many are forgettable. Some are performative. A few are genuinely consequential. This one has the potential to be the latter. At a time when public trust in institutions is low, civic dialogue is fragmented, and leadership conversations are increasingly reduced to slogans, TEDx Naples is positioning itself not as entertainment, but as a forum for adult thinking—about responsibility, justice, resilience, and what it means to lead in a world shaped by consequence rather than applause. This editorial explains why this particular TEDx event matters, what differentiates it from the broader TEDx ecosystem, and why its timing—and location—are not incidental.

What looks like cultural chaos—celebrity outrage cycles, travel exhaustion, and climate anxiety—is actually one interconnected signal. Entertainment, mobility, and climate stress now operate as a single feedback loop, revealing how systemic overload shows up first in culture before it appears in policy or economics.

As Arctic ice retreats, Greenland has shifted from geographic periphery to strategic center. Climate change is exposing new shipping routes, military corridors, and critical mineral reserves—placing Greenland at the intersection of great-power competition, environmental collapse, and unresolved questions of sovereignty and self-determination.