Racial colour was engineered, formalised, and institutionalised over centuries, and it continues to shape how people of African descent understand themselves and one another across continents, often to their own detriment.

The confusion between the words“Black” and “African” is not a matter of semantics, preference, or generational sensitivity. It is the result of a historical compression that collapses ancestry, geography, civilisation, and political power into a single chromatic label, stripping meaning from identity while pretending to unify it. This compression did not occur naturally. It was engineered, formalised, and institutionalised over centuries, and it continues to shape how people of African descent understand themselves and one another across continents, often to their own detriment.

Africa existed as a civilisational reality tens of thousands of years before race existed as an organising principle. Archaeological, genetic, and anthropological evidence confirms that the African continent is the birthplace of modern humanity, with uninterrupted human presence stretching back at least three hundred thousand years. Over this vast span of time, Africans organised themselves not through colour but through lineage, language, land, cosmology, profession, and political belonging. Kingdoms rose and fell, trade routes connected Africa to the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Asia, and sophisticated systems of governance, law, education, metallurgy, agriculture, and architecture flourished. Identity was relationaland contextual, rooted in who one’s people were, where one came from, and howone belonged within a social order. Skin tone existed, but it did not determine humanity, destiny, or value.

Race, by contrast, is a modern invention. The concept of “Black” as a racial identity emerged between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries alongside European colonial expansion andthe transatlantic slave trade. Prior to this period, Europeans primarily categorised difference through religion, nationality, and language rather than race. The large-scale enslavement of Africans required a new logic, one that could justify permanent, inheritable bondage while maintaining moral distance from its violence. “Blackness” became that logic. It was not merely descriptive but administrative, encoded into law, commerce, census records, property rights, and social hierarchy. To be Black was not to belong to a culture or a people, but to occupy a position within a racial caste system defined in opposition to whiteness.

This distinction matters because the word “Black” did not originate within African societies, nor did it reflect how Africans understood themselves. It was imposed from the outside and designed toserve economic and political ends. When Africans today resist being called Black, that resistance is often misinterpreted as denial, internalised racism,or elitism. In reality, it is frequently an insistence on accuracy. To call an Ethiopian, a Nigerian, a Senegalese, and a South African simply “Black” is to erase thousands of years of divergent histories, languages, spiritual traditions, and social structures, replacing them with a racial shorthand forged in a colonial context. It is to substitute civilisation with colour.

For many Africans, the term “Black” carries meanings shaped primarily by the history of racialisation in the Americas and Europe rather than by African historical experience itself. While Africa was deeply scarred by colonialism, partition, and extraction, most African societies were not structured internally around a Black–white racial binary. Identity was not built through opposition to whiteness, because whiteness was not the organising centre of African social life. To insist that African identity must pass through the category of Blackness is to universalise a Western racial framework and apply it retroactively to a continent that predates it by millennia.

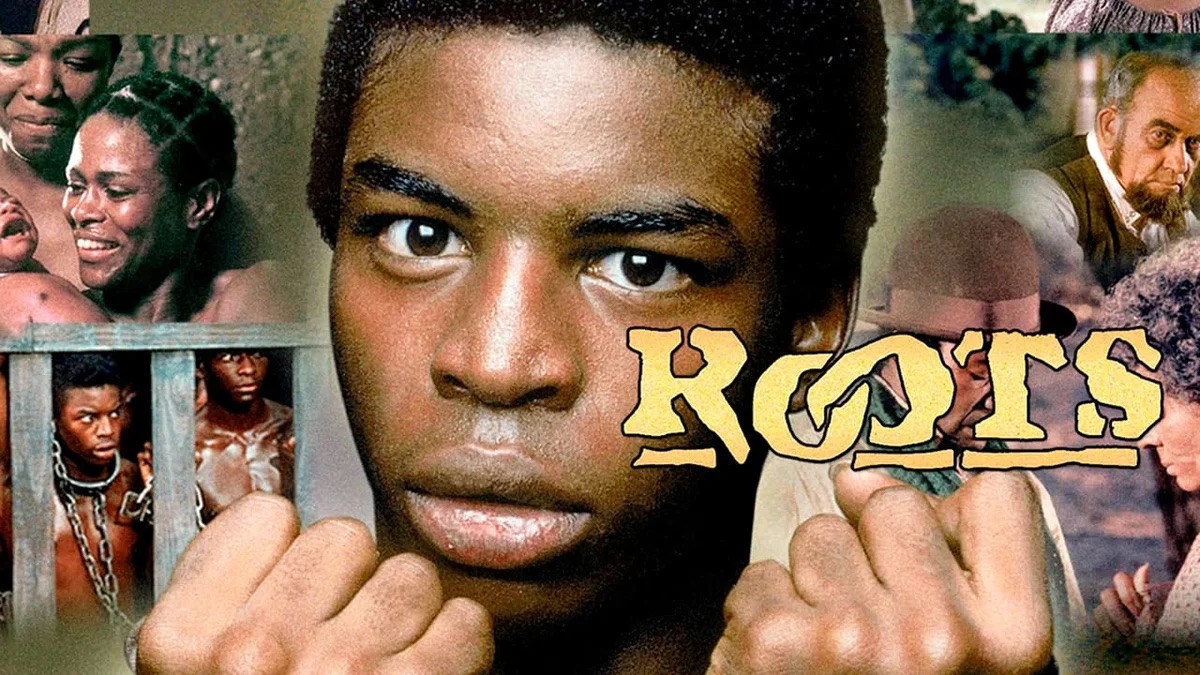

At the same time, dismissing Black identity altogether would be equally inaccurate. Black American identity, in particular, is not a diluted or failed version of African identity, as it is sometimes portrayed, but a distinct peoplehood forged under extraordinary conditions. Enslaved Africans in the Americas were violently stripped of specific ethnic affiliations, languages, and kinship networks, then forced to reconstruct meaning under surveillance, exclusion, and legal non-personhood. What emerged from that history was not cultural absence but cultural synthesis. New languages developed with their own grammatical systems, new spiritual practices took shape, and entirely new artistic, musical, and philosophical traditions were created. Black American culture is not African culture preserved intact, nor is it European culture adopted wholesale. It is a civilisation born under constraint, marked by resilience, innovation, and collective memory.

The misunderstandings between Africans and Black Americans arise largely from treating these different historical processes as if they were interchangeable. Africans may perceive Black Americans as overly focused on race, not always recognising how thoroughly race structures everyday life, opportunity, and safety in the United States. Black Americans may perceive Africans as distant from racial struggle, not always recognising that colonialism, ethnic stratification, and imperial domination produced different but equally complex systems of power and survival across the continent. These are not failures of empathy so much as failures of historical literacy.

Even cultural debates that appear superficial, such as disagreements over hair, masculinity, or respectability, are deeply rooted in this shared but uneven history. Many African societies historically braided male hair, assigning styles based on age, status, spiritual role, or rite of passage. Colonial administrations and missionaries systematically criminalised African aesthetics, imposing European standards of appearance and rigid gender norms while associating African self-expression with primitiveness or moral deficiency. In the post-colonial period, especially within the diaspora, these imposed standards often hardened into respectability politics, driven by fear that deviation would invite discrimination or danger. What is sometimes defended as tradition is, in many cases, colonial residue misremembered as cultural law.

Across the global African diaspora, experiences of identity vary widely depending on local histories of enslavement, colonisation, migration, and racial classification. Brazil, the Caribbean, Europe, and North America each developed distinct racial systems that shaped how African descendants were categorised, controlled, and allowed to belong. There is no singular diasporic experience, just as there is no singular African identity. Attempts to flatten this complexity in the name ofunity often reproduce the very erasures they claim to oppose.

The deeper truth, and the one most often avoided, is that Africa is ancestral, Blackness is political, and the diaspora is adaptive. These realities are interconnected but not interchangeable. Confusing them does not create solidarity; it creates friction,projection, and misplaced grievance. Weaponising them sustains old hierarchies under new language. Clarity, not simplification, is the foundation of dignity.

This distinction matters because language shapes how power is distributed, how policies are written, how histories are taught, and how people recognise themselves in one another. When identity is misnamed, people are forced to live inside definitions that were never designed for their liberation. Africa is not a colour. Black is not a birthplace. Understanding the difference is not an act of division but an act of intellectual honesty, and intellectual honesty is the first requirement for any future built on mutual respect rather than inherited confusion.

That is why this matters.

On February 8, 2026, Bad Bunny — Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio — stood at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California and delivered what will likely be remembered as one of the most consequential Super Bowl halftime performances of the 21st century. More than a show, it was a statement of identity, belonging, and cultural force — a moment where music intersected with global discourse and collective self-recognition.

For the past two decades, business has lived under a spell — the belief that technology is the ultimate disruptor. We’ve worshipped at the altar of innovation, measuring success by how quickly we could automate, digitise, and optimise. Tech has indeed changed the way we live, work, and connect. But here’s the inconvenient truth: In the next decade, technology won’t be the competitive advantage. Trust will.

Christchurch is not a city that performs for visitors. It does not overwhelm with spectacle, nor does it curate itself for instant gratification. Instead, it reveals itself slowly—through land, infrastructure, history, and conversation. That becomes clear the moment you sit down, coffee in hand, in the gardens of Chateau on the Park and begin talking to someone who has lived the city from the inside. Christchurch is often described as the most “English” city in New Zealand, but that shorthand misses what actually defines it. This is a city shaped by settlement decisions, seismic consequences, social memory, and resilience under pressure. It is flat because it was built on swamp land. It is orderly because it inherited British systems. It is cautious because it has been physically broken before. You don’t understand Christchurch until you understand what it has endured—and how it continues to function anyway.